Kings Cross underpass rotated, London

In the last post we covered some basic operations with cloud machines, in this post we discuss using Docker containers to replicate environments in the cloud and how to containerise a Jupyter notebook.

Docker has become a standard way to package applications enabling something that runs on one machine to run on another. It is a container which holds a virtualisation of an operating system within which applications can be packaged to allow them to move between machines. In a way it’s a heavier duty version of python virtual environments going beyond python to cover a wider range of dependencies. This post looks at:

1. Building a Docker container for the notebook

2. Running the container and saving it

3. Accessing the container in the cloud and running it

4. Other useful Docker commands

1. Building a Docker container for the notebook

Below is an example of a Dockerfile that will create a container with a Jupyter notebook.

We can create this in a file $ nano Dockerfile in a folder Notebook_example where we will be working locally. The text below is pasted into the Dockerfile.

These commands start with a base anaconda environment, and then imports python and jupyter. A notebook which we have locally

Dockerised_notebook.ipynb is then copied into the container and run to output to the container’s port 8009.

# We start with a Miniconda base image

FROM continuumio/miniconda:latest

# Update condas

RUN conda update --all

# Install python and a series of condas libraries

RUN /opt/conda/bin/conda update -n base -c defaults conda && \

/opt/conda/bin/conda install python=3.7 && \

/opt/conda/bin/conda install anaconda-client && \

/opt/conda/bin/conda install jupyter -y

# Creates a folder for the notebook

RUN mkdir notebooks

# Copy the notebook from the local machine to the notebooks folder

COPY Dockerised_notebook.ipynb /notebooks/

# Switch the working directory to notebooks

WORKDIR /notebooks

# Run the notebook on container port 8009

CMD ["jupyter", "notebook", "--port=8009", "--no-browser", "--ip=0.0.0.0", "--allow-root"]

To build the docker image from the docker file we run the command below. The –tag gives the image a name containerised_notebook. Here the command is run from outside the folder Notebook_example which contains the Docker file.

$ docker build --tag containerised_notebook Notebook_example

This build stage will take a while as there are several things to install. Building the Docker file creates a Docker image. A Docker image is a blueprint/template that enables you to generate a Docker container by running it.

2. Running the container and saving it

To run the container a command of the general form below is used (Adding a -d flag runs the container in the background). The p flag maps the container port to a local port on the computer

$ docker run -p localport:containerport image_id (or image_name)

As a specific example in the command below we are running the containerised image on the local machine (The container is outputting to port 8009 and this is then sent to 8009 on the local machine)

$ docker run -p 8009:8009 --init containerised_notebook

Paste the hyperlink with the token that is generated in the browser and the notebook which is running in the container will be visible on the local computer at http://localhost:8009.

Checks to do if the notebook is not visible:

- That the port number in the notebook’s url is the number that the container is being sent to on the local machine i.e. the left-hand number of local_machine_port:container_port

- If port 8009 is already in use on the machine, another local machine port should be used

Having tested that the container runs we can stop it running with the command below. This will remove any contents generated by the container, but keep the container.

$ docker stop container_id (or container_name)

If you want to delete the container this can be done with $ docker rm container_id (or container_name)

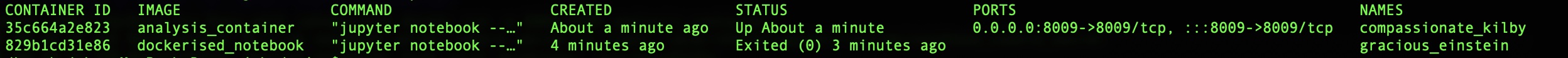

Listing the containers that have run or are running

To see the container images that have been created (both the stopped containers and the running) use:

$ docker ps -a

If you only want to see running containers drop the -a. An example of what this comand returns is given below, showing a stopped and running container with the image names and ids. The container ids and names are automatically generated as they weren’t specified when running the containers.

Pushing the container image to a Docker registry so it is accessible

Having built the container and checked that it works we push the image to a container registry to store it and so we can access it from somewhere else like the cloud or another computer.

Here we use Docker Hub and the examples assume you have an account on Docker Hub and are logged in on it, but there are other container registry options such as the GitHub Container registry and Amazon’s Elastic Container Registry.

The Docker Hub account name is used to identify the container and should be included in the tag when it is built e.g. $ docker build --tag docker_account_name/containerised_notebook after this it can be pushed with:

$ docker push docker_account_name/containerised_notebook

Now when we want to use it we can pull the container down to any computer that has Docker and it should run.

3. Accessing the notebook in the cloud

In what follows we have set up a virtual machine in the cloud and ssh’d into it.

3.1 Setting up Docker on the cloud machine and accessing the container

If Docker is not already installed on the cloud machine trying to run it will fail and you will be prompted to install it. On the Ubuntu instance used in this example

the installation command is $ sudo snap install docker.

When installed on the virtual machine run the below and then log out to add running Docker to the permissions of the current user when they input their password. The first command creates a group called docker, the second adds the current user to the group.

$ sudo groupadd docker

$ sudo usermod -a -G docker $USER

Having done this you can pull the image we have just produced down from Docker Hub onto the virtual machine and run it.

$ sudo docker pull docker_account_name/containerised_notebook

3.2 Accessing the notebook via port forwarding

The Jupyter notebook is creating a webpage as a user interface. This does not raise an issue on a local machine as only the computer user can use it, but in the context of a cloud

machine it is problematic as on the public internet in principle others can use the notebook to run commands on the virtual machine. We therefore need to access it in a secure way.

In the first tutorial we used a firewall with ssh access only to lock down the ports of the machine. To access the machine through this we run the notebook back through the ssh connection using port forwarding. This means the notebook can only be accessed from the laptop where we have the ssh key.

Here we have the containerised notebook in the cloud outputting to 8009. This is then passed through the firewall via ssh (see the discussion of how the firewall was set up in part 1) and forwarded to the port localhost:8009 where we can access it via a web browser. The general form of local port forwarding which we run from the local machine is:

$ ssh -L local_port:destination_server_ip:remote_port ssh_server_hostname

Looking at a specific example, where we are working on a virtual machine with the user account cloud_user at the following IP address cloud_user@178.62.108.102

$ ssh -i private_key/filepath -L 8009:localhost:8009 cloud_user@178.62.108.102

The -L flag is used as we are forwarding a port (8009) from the local machine to the corresponding port on the cloud machine creating a tunnel via the ssh connection and then run the container from the cloud machine through it to the local machine. If as before, but now from the cloud machine, we run the container using the command below and send its output to 8009 then port forwarding will make this accessible at 8009 on the local machine via ssh.

$ docker run -p 8009:8009 --init containerised_notebook

If you copy and paste the link generated the hyperlink with the token into the browser on the local computer and the notebook should be visible.

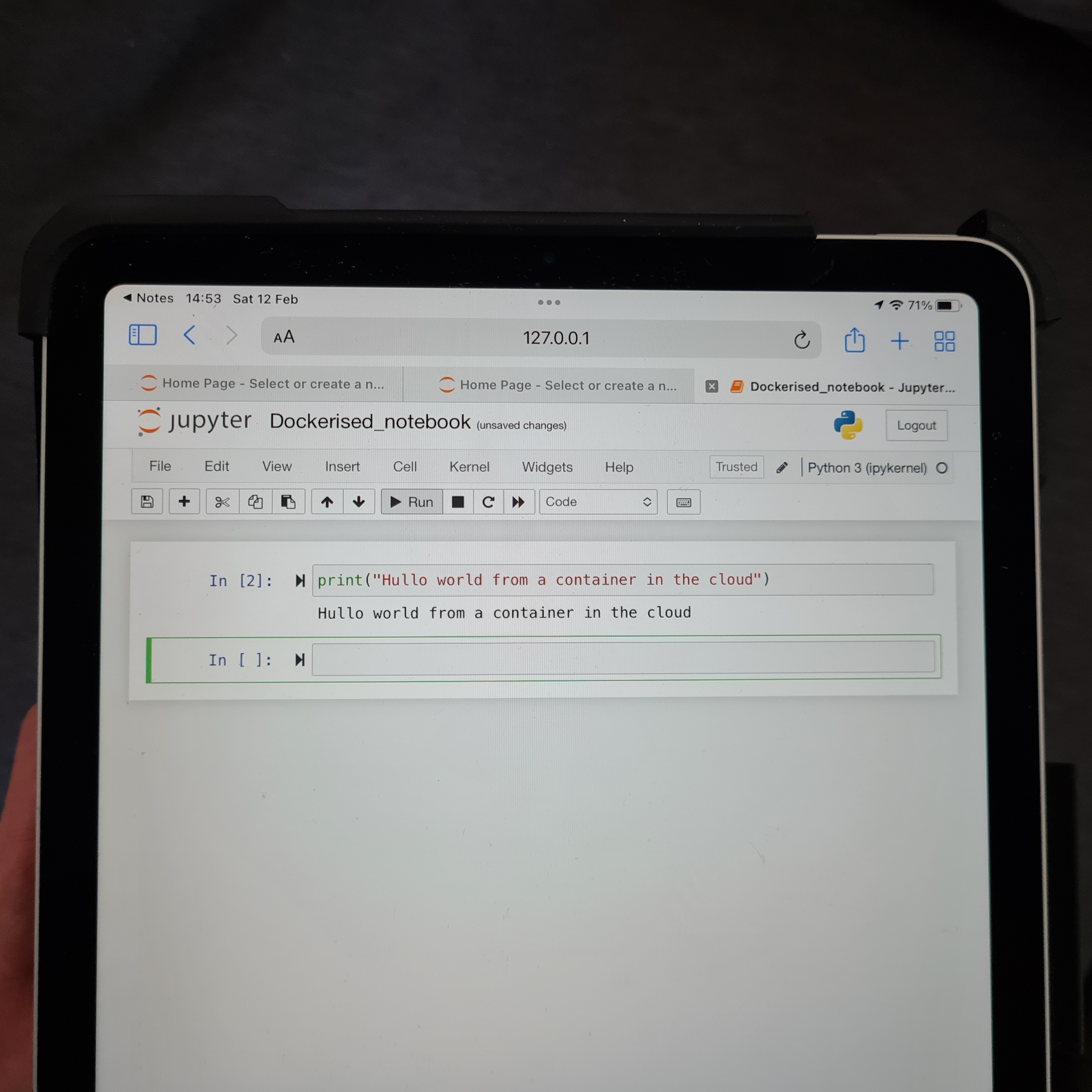

Below is an example of an iPad accessing a Jupyter notebook running on a container on a virtual machine in the cloud via port forwarding with the Termius app.

4. Other useful Docker commands

We have built a container image and then run the image to produce a container, below are some other useful commands to know when working with Docker containers.

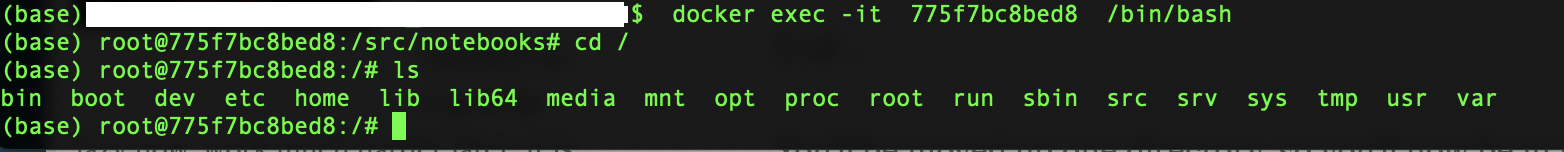

Logging into the container

The container contains its own simulated operating system and file structure independently of the computer it is being run on. For example in the container above there is a folder notebooks inside the container which holds the jupyter notebook. To log into a running container:

$ docker exec -it container_id (or container_name) /bin/bash

After this one can navigate around, like a normal Linux based system. Below is an example of this, where a running container has been logged into and then its internal file structure shown.

To exit the container and go back to the machine it is run from type

To exit the container and go back to the machine it is run from type exit from the command line of the container.

Restarting a container

Unlike run which rebuilds the container from scratch, start allows you to log back into the container that has been stopped

$ docker start -ia container_id (or container name)

Saving the container

This saves a container’s files to a new image. It does not save data contained inside the container.

$ docker commit container_id docker_user_name/name_of_saved_image:version_no

The below saves the image to a tar file

$ docker save container_name > container_name.tar # Save to a tar file

To load an image from a tar file use the command docker load.

Exporting data from the container

The following command will given a container_id and a filepath to the file inside the container you want to copy, copy it to the location specified by the destination_file_path on the local system.

$ docker cp container_id:/file/path/within/container /destination_file_path

Cloud posts:

Cloud 1: Introduction to launching a Virtual Machine in the Cloud

Cloud 2: Getting started with using a Virtual Machine in the Cloud

Cloud 3: Docker and Jupyter notebooks in the Cloud

Cloud 5: Introduction to deploying an app with simple CI/CD

Cloud 6: Introduction to Infrastructure as Code using CloudFormation

Cloud 7: Building an API with Lambda, Docker and CloudFormation

Cloud 8: Automating publishing an Android app to Google Play with GitHub Actions

References